In his 2004 paper in Trends in Ecology and Evolution, Steven Peck argues:

Simulation models can be used to mimic complex systems, but unlike nature, can be manipulated in ways that would be impossible, too costly or unethical to do in natural systems. Simulation can add to theory development and testing, can offer hypotheses about the way the world works and can give guidance as to which data are most important to gather experimentally.

A sentiment I agree with fully. However, another important use of simulation is in the experimentation phase of model development before confronting models with data. In ecology, epidemiology and related fields, it is common to have observational data (as opposed to controlled, randomized experiments). In these situations, two questions need to be asked:

- What can we observe about the system? (ie what will the data look like?)

- Given what we can observe (1), will our model(s) be able to capture the underlying process and parameters?

In order to answer these questions, we need to be able to simulate the hypothesized processes and use the simulated observations to fit our model(s). This process has the additional benefit of forcing us to understand the process that we are modelling. In fact, I find that the act of formalizing the hypothesized process into a coded simulation makes the formulation of the likelihood function more straightforward.

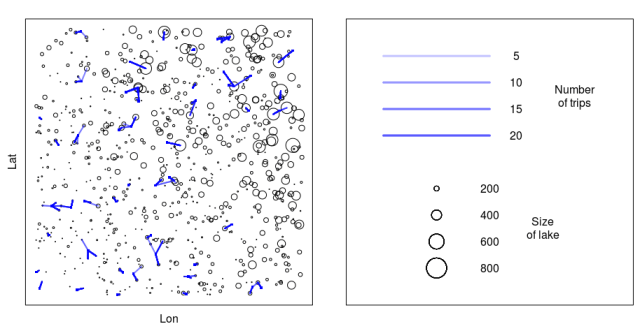

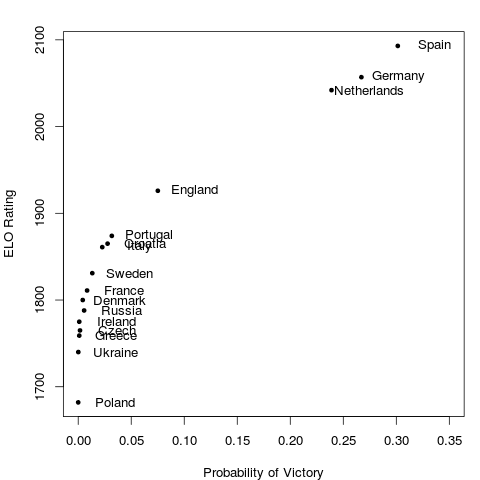

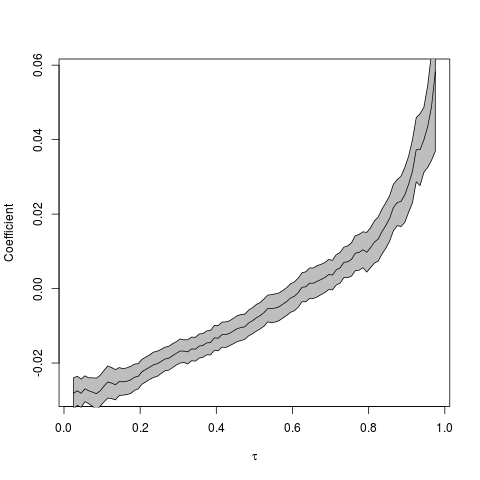

Let’s look at an example. In a recent paper in the Journal of Applied Ecology, we model the trip taking behaviour of recreational boaters in Ontario. Through a survey, we observed the trip outcomes of a sample of boaters. We wanted to compare two models of the trip taking process (see the paper for model descriptions).

###############################

##### RUM v GM sim tests ######

##

## Corey Chivers, 2012

##

###############################

n_boaters<-50

n_lakes<-750

n_trips<-rpois(n_boaters,16)

euclidian<-function(from_x,from_y,to_x,to_y)

{

return( sqrt( (from_x-to_x)^2 + (from_y-to_y)^2 ) )

}

sim_boaters<-function(N=n_boaters)

{

##Home locations

return(as.matrix(cbind(runif(N,0,100),runif(N,0,100)) ))

}

sim_lakes<-function(N=n_lakes)

{

x<-cbind(runif(N,0,100))

y<-cbind(runif(N,0,100))

size<-abs(rnorm(N,x+y,x+y))

return(cbind(x,y,size))

}

get_d_mat<-function()

{

## matrix of boaterxlake distances

d_mat<-array(dim=c(n_boaters,n_lakes))

for(b in 1:n_boaters)

{

d_mat[b,]<-euclidian( boater[b,1],boater[b,2],lakes[,1],lakes[,2] )

}

return(d_mat)

}

sim_trips<-function(par,M)

{

trips<-list()

for(b in 1:n_boaters)

{

P<-M(par,b)

trips[[b]]<-sample(1:n_lakes,n_trips[b],p=P,replace=TRUE)

}

return(trips)

}

RUM<-function(par,b) ## par{b1,b2}

{

exp_sum_V<-sum(exp(par[1]*lakes[,3]+par[2]*d_mat[b,]) )

V<-exp(par[1]*lakes[,3]+par[2]*d_mat[b,])

p_j<-V/exp_sum_V

return(p_j)

}

GM<-function(par,b) ## par{e,d}

{

Ai<-sum(lakes[,3]^(par[1]) * d_mat[b,]^(-par[2]))

WD<-lakes[,3]^(par[1]) * d_mat[b,]^(-par[2])

p_j<-WD/Ai

return(p_j)

}

ll<-function(par,M,data,give_neg=-1)

{

ll<-0

ll<-sapply(1:n_boaters,function(b){

P_b<-M(par,b)

l_tmp<-0

for(t in 1:length(data[[b]]))

l_tmp<-l_tmp+log(P_b[ data[[b]][t] ] )

return(l_tmp)

})

return(give_neg*sum(ll))

}

dAIC<-function(ll)

{

delta_aic<-numeric(length(ll[,1]))

for(i in 1:length(ll[,1]))

{

delta_aic[i]<-(2*ll[i,2]+(2*n_par))-(2*ll[i,1]+(2*n_par))

}

return(delta_aic)

}

plot_trips<-function(col='green',add_trips=TRUE,pdffile=NULL)

{

if(!is.null(pdffile))

pdf(pdffile)

par(mgp=c(0.5,0,0),cex=1.2,mfrow=c(1,2),mar=c(1,2,1,0.5),pty='s')

col=rgb(0,0,1,0.05)

plot(lakes[,1],lakes[,2],cex=lakes[,3]/200, xlab='Lon', ylab='Lat',xaxt='n',yaxt='n')

if(add_trips)

{

for(i in 1:n_boaters)

{

for(tr in 1:length(trips[[i]]))

{

segments(boater[i,1],boater[i,2],lakes[trips[[i]],1],lakes[trips[[i]],2],col=col,lwd=2)

}

points(boater[i,1],boater[i,2],pch=15,col='blue',cex=0.5)

}

}

### Make a legend ###

plot(1,1,col='white', xlab='', ylab='',xaxt='n',yaxt='n',xlim=c(0,1),ylim=c(0,1))

yloc<-c(0.9,0.8,0.7,0.6)

n_tr<-c(5,10,15,20)

for(i in 1:4)

{

for(n in 1:n_tr[i])

segments(0.1,yloc[i],0.5,yloc[i],col=col,lwd=3)

text(0.6,yloc[i],n_tr[i])

}

text(0.82,0.75,"Number\nof trips")

yloc<-c(0.4,0.3,0.2,0.1)

l_size<-c(200,400,600,800)

for(i in 1:4)

{

for(n in 1:n_tr[i])

points(0.3,yloc[i],cex=l_size[i]/200)

text(0.5,yloc[i],l_size[i])

}

text(0.7,0.25,"Size\nof lake")

if(!is.null(pdffile))

dev.off()

}

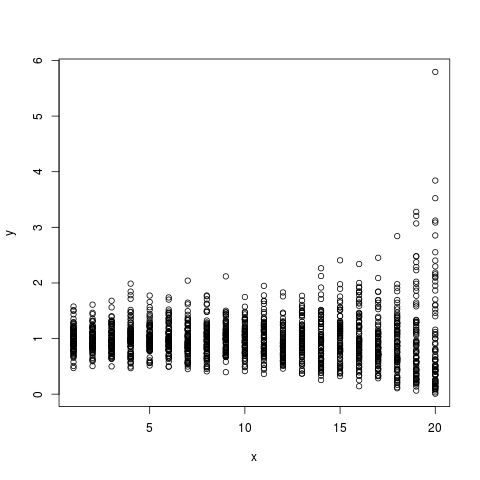

With all of the relevant functions defined, we then simulate behaviour under each model, fit to each model and compare our ability to both capture the generating parameter values and to distinguish between the competing models.

boater<-sim_boaters()

lakes<-sim_lakes()

d_mat<-get_d_mat()

n_sims<-1000

n_par<-2

save_par<-array(dim=c(n_sims,2*n_par))

ll_save<-array(dim=c(n_sims,2))

### RUM GENERATING ###

for(i in 1:n_sims)

{

lakes<-sim_lakes()

d_mat<-get_d_mat()

## pars{b1,b2}

pars<-c(runif(1,0.01,0.1),runif(1,-10.5,-1.5))

trips<-sim_trips(pars,RUM)

opt<-optim(pars,ll,M=RUM,data=trips)

save_par[i,]<-c(pars,opt$par)

pars<-c(0.5,1,0,0) #seeds

opt2<-optim(pars,ll,M=GM,data=trips)

ll_save[i,]<-c(opt$value,opt2$value)

print(i)

}

par(mfrow=c(1,2),pty='s')

plot(ll_save)

abline(0,1,lty=2)

hist(dAIC(ll_save))

ll_saveRUM<-ll_save

save_parRUM<-save_par

par(mfrow=c(2,2),pty='s')

param_names<-c('B1','B2')

for(i in 1:n_par)

{

plot(save_parRUM[,i],save_parRUM[,i+n_par],xlab=paste('Generating ',param_names[i]),ylab=paste('Fit ',param_names[i]))

abline(0,1)

}

### GM GENERATING ###

for(i in 1:n_sims)

{

lakes<-sim_lakes()

d_mat<-get_d_mat()

## par{e,d}

e<-runif(1,0.1,0.9)

d<-runif(1,1,5)

pars<-c(e,d)

trips<-sim_trips(pars,GM)

opt<-optim(pars,ll,M=GM,data=trips)

save_par[i,]<-c(pars,opt$par)

pars<-c(0.001,-2) #seeds

opt2<-optim(pars,ll,M=RUM,data=trips)

ll_save[i,]<-c(opt$value,opt2$value)

print(i)

}

x11()

par(mfrow=c(1,2),pty='s')

plot(ll_save)

abline(0,1,lty=2)

hist(dAIC(ll_save))

ll_saveGM<-ll_save

save_parGM<-save_par

par(mfrow=c(2,2),pty='s')

param_names<-c('e','d')

for(i in 1:n_par)

{

plot(save_parGM[,i],save_parGM[,i+n_par],xlab=paste('Generating ',param_names[i]),ylab=paste('Fit ',param_names[i]))

abline(0,1)

}

### Plot deltaAIC distributions ###

par(mfrow=c(1,2),pty='s')

hist(dAIC(ll_saveGM),breaks=30)

hist(dAIC(ll_saveRUM),breaks=30)

plot_trips()

After verifying that we can both distinguish between the two models, and can recapture the generating parameters, we then use simulation, in the manner described by Peck (2004), to analyse the implications of using alternative models of boater behaviour on the spread of invasive species.

Insights derived from simulation need to be complimented with controlled, randomized experiments. However, the use of simulation as a laboratory for the statistical modeller is indispensable, and you can do it all without putting a white coat on – unless you’re into that kind of thing.