The excellent BBC podcast More or Less does a great job at communicating and demystifying statistics in the news to a general audience. While listening to the most recent episode (Is Salt Bad for You? 19 Aug 2011), I was pleased to hear the host offer a clear, albeit incomplete, explanation of p-values, as reported in scientific studies like the ones being discussed in the episode. I was disappointed, however, to hear him go on to forward an all too common fallacious extension of their interpretation. I count the show’s host, Tim Harford, among the best when it comes to statistical interpretation, and really feel that his work has improved public understanding, but it would appear that even the best of us can fall victim to this little trap.

The trap:

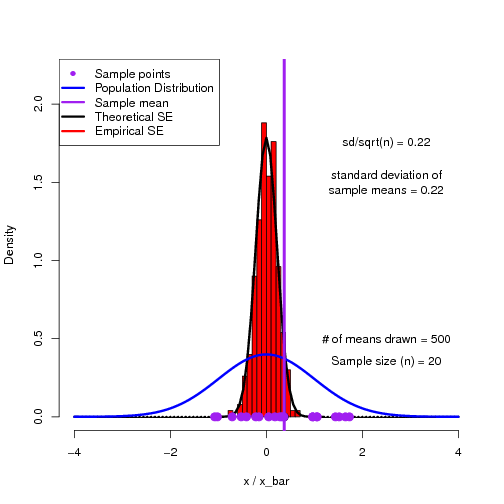

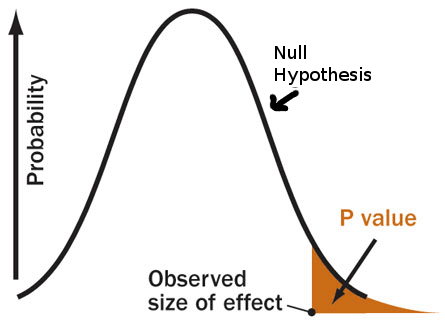

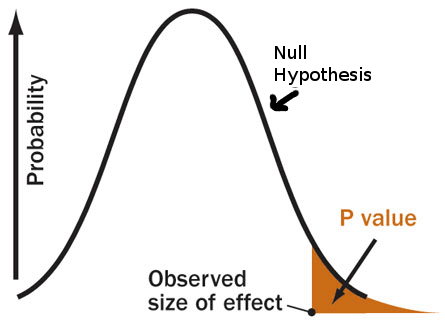

When conducting Frequentist null hypothesis significance testing, the p-value represents the probability that we would observe a result as extreme or more (this was left out of the loose definition in the podcast) than our result IF the null hypothesis were true. So, obtaining a very small p-value implies that our result is very unlikely under the null hypothesis. From this, our logic extends to the decision statement:

“If the data is unlikely under the null hypothesis, then either we observed a low probability event, or it must be that the null hypothesis is not true.”

It is important to note that only one of these options can be correct. The p-value tells us something about the likelihood of the data, in a world where the null hypothesis is true. If we choose to believe the first option, the p-value has direct meaning as per the definition above. However, if we choose to believe the second option (which is traditionally done when p<0.05), we now believe in a world where the null hypothesis is not true. The p-value is never a statement about the probability of hypotheses, but rather is a statement about data under hypothetical assumptions. Since the p-value is a statement about data when the null is true, it cannot be a statement about the data when the null is not true.

How does this pertain to what was said in the episode? The host stated that:

How does this pertain to what was said in the episode? The host stated that:

“…you could be 93% confident that the results didn’t happen by chance, and still not reach statistical significance.”

Referring to the case where you have observed a p-value of 0.07. The implication is that you would have 1-p=0.93 probability that the null is not true (ie that your observations are not the result of chance alone). From the discussion above, we can begin to see why this cannot be the case. The p-value is a statement about your results only when the null hypothesis is true, and therefor cannot be a statement about the probability that it is false!

An example:

With our complete definition of the p-value in mind, lets look at an example. Consider a hypothetical study similar to those analyzed by the Cochrane group, in which a thousand or so individuals participated. In this hypothetical study, you observe no mean difference in mortality between the high salt and low salt groups. Such a result would lead to a p-value of 0.5, or 50%. Meaning that if there is no real effect, there is a 50% chance that you would observe a result greater than zero, however slightly. Using the incorrect logic, you would say:

“I am 50% confident that the results are not due to chance.”

Or, in other words, that there is a 50% probability that there is some adverse effect of salt. This may seem reasonable at first blush, however, consider now another hypothetical study in which you have recruited just about every adult in the population, (maybe you’re giving away iPads or something), and again you observe zero mean difference in mortality between groups. You would once again have a p-value of 0.5, and might again erroneously state that you are 50% confident that there is an effect. After some thought, however, you would conclude that the second study provided you with more confidence about whether or not there is any effect than did the first, by virtue of having measured so many people, and yet your erroneous interpretation of the p-value tells you that your confidence is the same.

The solution:

I have heard this fallacious interpretation of p-values everywhere from my undergraduate Biometry students, to highly reputable peer reviewed research publications. Why is this error so prevalent? It seems to me that the issue lies in the fact that what we really want to be able to say is not a statement about our results under the assumption of no effect (the p-value), but rather a statement about hypotheses given our results (which we do not get directly through the p-value).

One solution to this problem lies in a statistical concept known as power. Power is the calculation of how likely it is that you would observe a p-value below some critical value (usually the canonical 0.05), for both a given sample size and the size of the effect that you wish to detect. The smaller the size of the real effect that you wish to measure, the higher the sample size required if you want to have a high probability of finding statistical significance.

This is why it is important to distinguish, as was done in the episode, between statistical significance, and biological, or practical significance. A study may have high power, due to a large sample size, and this can lead to statistically significant results, even for very small biological effects. Alternatively the study may have low power, in which case it may not find statistically significant results, even if there is indeed some real biologically relevant effect present.

Another solution is to switch to a Bayesian perspective. Bayesian methods allow us to make direct statements about what we are really interested in – namely, the probability that there is some effect (general hypotheses), as well as the probability of the strength of that effect (specific hypotheses).

In short:

What we really want is the probability of hypotheses given our data (written as P(H | D) ), which we can obtain by applying Bayes rule.

What we get from a p-value is the probability of observing something as extreme or more than our data, under the null hypothesis ( written as P(x>=D | Ho) ). Isn’t that awkward? No wonder it is so commonly misrepresented.

So, my word of caution is this: We have to remember that the p-value is only a statement of the likelihood of making an observation as extreme or more than your observation, if there is, in fact, no real effect present. We must be careful not to perform the tempting, but erroneous, logical inversion of using it to represent the probability that a hypothesis is, or is not true. An easy little catch phrase to remember this is:

“A lack of evidence for something is not a stack of evidence against it.”