I love board games. Over the holidays, I came across this interesting post over at Arthur Charpentier’s Freakonometrics blog about the classic game of snakes and ladders. The post is a nice little demonstration of how the game can be formulated completely as a Markov chain, and can be analysed simply using the mathematics of state transitions.

The particular board which was analysed had the following ‘portals’:

starting=c(4,9,17,20,28,40,51,54,62,64,63,71,93,95,99) ending=c(14,31,7,38,84,59,67,34,19,60,81,91,73,75,78)

Given that a player roles a six sided die to determine how many positions forward to travel, the transition matrix can be defined as:

n=100

M=matrix(0,n+1,n+1+6) ## from n+1 starting positions (0-100 inclusive) to n+1+6 ending (includes overshooting the last position)

rownames(M)=0:n

colnames(M)=0:(n+6)

for(i in 1:6){diag(M[,(i+1):(i+1+n)])=1/6} ##dice role probs from each position on the board

M[,n+1]=apply(M[,(n+1):(n+1+6)],1,sum) ##collect all of the 'overshooting' the ending probabilities

M=M[,1:(n+1)]

for(i in 1:length(starting))

{

v=M[,starting[i]+1]

ind=which(v>0)

M[ind,starting[i]+1]=0

M[ind,ending[i]+1]=M[ind,ending[i]+1]+v[ind]

}

In order to calculate the probability distribution of a player’s position after h rolls, the initial position vector (what state is currently occupied) is multiplied by the transition matrix raised to the hth power.

### Multiply the transition matrix to get the position distribution ###

powermat<-function(P,h){

Ph<-P

if(h>1)

{

for(k in 2:h)

{

Ph<-Ph%*%P

}

}

return(Ph)

}

### -- ###

initial<-c(1,rep(0,n))

initial%*%powermat(M,h=1)

You can vary h and get the probability distribution of where a player will be on the board after that many rolls. Neat!

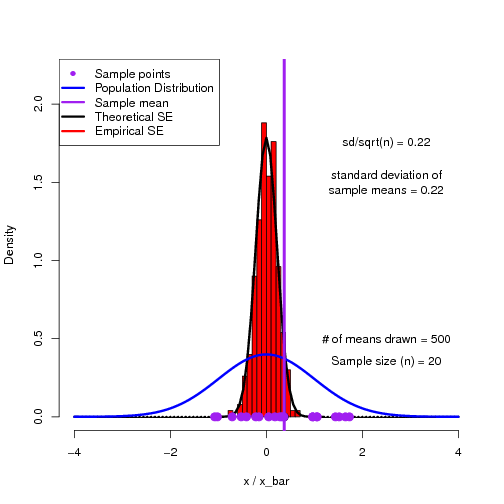

The thing is, this got me wondering… For the first roll, a player can end up in 1 of 6 possible positions (for this board 1,2,3,14,5 or 6), each with a 1/6 chance. We therefore can predict the position of a player after one roll with a good degree of confidence. If we wanted to predict the player’s position at roll 3, however, there are more positions which are possible (though not equally likely). So we would probably be less confident when trying to predict the position of a player after 3 rolls, and we would feel less and less confident the further out we get.

However, the game does end (although unfortunately for those who would like to move on to video games, this is not guaranteed – I leave it to the reader to prove this) and therefore we might expect to be fairly confident in predicting a player’s position after 100 rolls (they are probably at the finish line, of course). Which begs the question, how many rolls into a game would you be the least confident in predicting a player’s position?

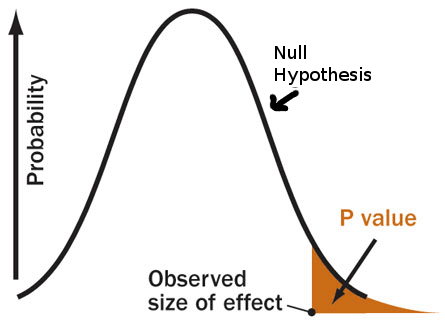

To answer this question, we need a measure of uncertainty which can quantify how well we could predict a player’s position. It turns out, that the Shannon entropy measure does just that! The formula is very simple:

H=-∑p log(p)

entropy<-function(p){

ind<-which(p>0)

return(-sum(p[ind]*log(p[ind])))

}

The Shannon entropy defines how much information is missing about the outcome of a random variable. So, if there is no information missing, we know the outcome with p=1, and the Shannon entropy = 0. If a random variable can have n possible outcomes, then the Shannon entropy is at a maximum when p=1/n for each.

So, back to my question: how many rolls into a game is our uncertainty about a player’s position on the board at a maximum? Keep in mind that we are talking about uncertainty with respect to our predictions before the game is started. Any knowledge of a player’s position at any point in the game would of course change our predictions and associated uncertainty. To answer this question, we just need to calculate the Shannon entropy of the outcome distribution generated by our Markov chain, and find at which point it is maximised.

##############################################################

############ Calculate the entropy after n turns #############

entropy<-function(p)

{

ind<-which(p>0)

return(-sum(p[ind]*log(p[ind])))

}

turns<-100

ent<-numeric(turns)

for(n in 1:turns)

ent[n]<-entropy(initial%*%powermat(M,n))

plot(ent,type='b',xlab='Turn',ylab='Entropy')

Which is at a maximum (highest uncertainty) at roll 10. We are most certain of a player’s position at roll 1 as we might expect, but again from rolls 33 and on. After which, we become increasingly certain that the player has reached the finish line.

TL;DR When predicting player positions in snakes and ladders, forecasts are least reliable ten rolls in. Have fun!