In a previous post, I demonstrated how to use my R package MHadapive to do general MCMC to estimate Bayesian models. The functions in this package are an implementation of the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm. In this post, I want to provide an intuitive way to picture what is going on ‘under the hood’ in this algorithm.

The main idea is to draw samples from a distribution which you can evaluate at any point, but not necessarily integrate (or at least, you don’t want to). The reason that integration is important come from Bayes theorem itself:

P(θ|D)=P(D|θ)P(θ)/P(D)

Where P(D) is the unconditional probability of observing the data. Since this is not dependant on the parameters of the model (θ) on which we wish to perform inference, P(D) is effectively a normalising constant which makes P(θ|D) a proper probability density function (ie. integrates to 1).

So, we have a non-normalised probability density function which we wish to estimate by taking random samples. The process of taking random samples itself is often difficult for complex models, so instead we explore the distribution using a Markov chain. We need a chain which, if run long enough, will consist as a whole of random samples from our distribution of interest (lets call that distribution π). This property of the Markov chain we are constructing is called ergodicity. The Metropolis-Hastings algorithm is a way to construct such a chain.

It works like this:

- Choose some starting point in the parameter space k_X

- Choose a candidate point k_Y ~ N(k_X, σ). This is often referred to as the proposal distribution.

- Move to the candidate point with probability: min( π(k_Y)/π(K_X), 1)

- Repeat.

The following code demonstrates this process in action for a simple normal target distribution.

################################################################

### Metropolis-Hastings Visualization #######

### Created by Corey Chivers, 2012 #########

################################################################

mh_vis<-function(prop_sd=0.1,target_mu=0,

target_sd=1,seed=1,iter=5000,plot_file='MH.pdf')

{

plot_range=c(target_mu-3*target_sd,target_mu+3*target_sd)

track <- NULL

k_X = seed; ## set k_X to the seed position

pdf(plot_file)

par(mfrow=c(3,1),mgp = c(1, 0.5, 0))

for(i in 1:iter)

{

track<-c(track,k_X) ## The chain

k_Y = rnorm(1,k_X,prop_sd) ## Candidate point

## -- plot kernal density estimation of the Chain

par(mar=c(0,3,2,3),xaxt='n',yaxt='n')

curve(dnorm(x,target_mu,target_sd),col='blue',lty=2,lwd=2,xlim=plot_range)

if(i > 2)

lines(density(track,adjust=1.5),col='red',lwd=2)

## -- plot the chain

par(mar=c(0,3,0,3))

plot(track,1:i,xlim=plot_range,main='',type='l',ylab='Trace')

pi_Y = dnorm(k_Y,target_mu,target_sd,log=TRUE)

pi_X = dnorm(k_X,target_mu,target_sd,log=TRUE)

## -- plot the target distribution and propsal distribution actions

par(mar=c(3,3,0,3),xaxt='s')

curve(dnorm(x,target_mu,target_sd),xlim=plot_range,col='blue',lty=2,ylab='Metropolis-Hastings',lwd=2)

curve(dnorm(x,k_X,prop_sd),col='black',add=TRUE)

abline(v=k_X,lwd=2)

points(k_Y,0,pch=19,cex=2)

abline(v=k_Y)

a_X_Y = (pi_Y)-(pi_X)

a_X_Y = a_X_Y

if (a_X_Y > 0)

a_X_Y = 0

## Accept move with a probability a_X_Y

if (log(runif(1))<=a_X_Y)

{

k_X = k_Y;

points(k_Y,0,pch=19,col='green',cex=2)

abline( v=k_X,col='black',lwd=2)

}

## Adapt the poposal

if(i>100)

prop_sd=sd(track[floor(i/2):i])

if(i%%100==0)

print(paste(i,'of',iter))

}

dev.off()

}

mh_vis()

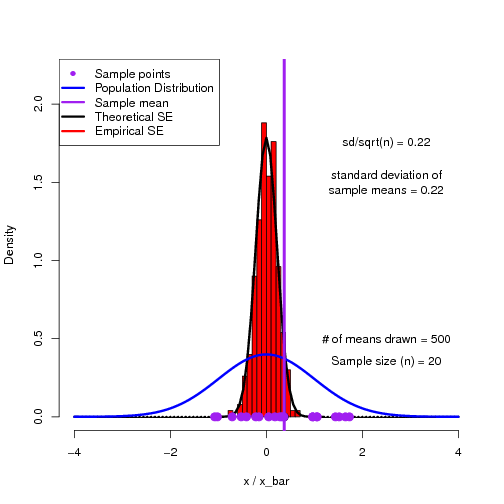

A common problem in the implementation of this algorithm is the selection of σ. Efficient mixing (the rate at which the chain converges to the target distribution) occurs when σ approximates the standard deviation of the target distribution. When we don’t know this value in advance. we can allow σ to adapt based on the history of the chain so far. In the above example, σ is simply updated to take the value of the standard deviation of some previous points in the chain.

The output is a multipage pdf which you can scroll through to animate the MCMC.

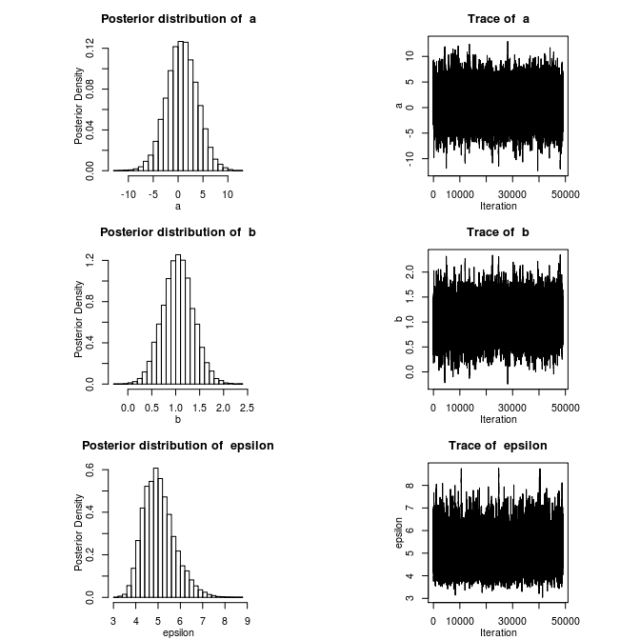

The top panel shows the target distribution (blue dotted) and a kernel smoothed estimate of the target via the MCMC samples. The second panel shows a trace of the chain, and the bottom panel illustrates the steps of the algorithm itself.

The top panel shows the target distribution (blue dotted) and a kernel smoothed estimate of the target via the MCMC samples. The second panel shows a trace of the chain, and the bottom panel illustrates the steps of the algorithm itself.

Note: notice the first 100 or so iterations were a rather poor representation of the target distribution. In practice, we would ‘burn’ the first n iterations of the chain – typically the first 100-1000.